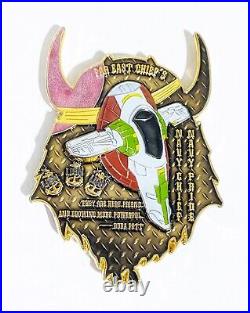

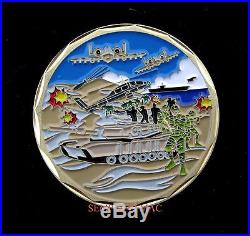

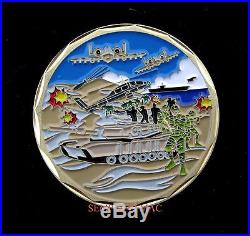

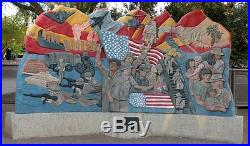

EXPERIENCE, QUALITY, AND SERVICE SINCE 1986. FROM A VETERAN OWNED COMPANY! Make us your source for your Custom US Military Hats, Pins, Patches, Coins, & Flags! Items are added daily, so bookmark this page & return often, for you will never know what we`ll have for sale from our stock of 14,000 items EEC2255! OPERATION DESERT STORM PATCH ARMY, NAVY, AIR FORCE, MARINES, COAST GUARD, COLLECTOR COIN! THIS COIN MEASURES TO BE 1 5/8 INCHES! Are you looking for a meaningful birthday, holiday, or anniversary gift for you or your Airman? This item is the perfect way to show case your loved ones military service and honor. This coin is a prized piece for any collection…. Especially for the Veteran or Love One, who has served or is still serving with pride! Order extras for friends & family to show your appreciation for your love one’s service to our country! Coins fuel for me a passion for Air Force history connected to their heritage, and although it’s a short heritage, it’s a pretty distinguished heritage. These Coins tie us back to our history, to the people who came before us, to all of the giants and to all of the little people who make the Air Force work day-to-day. That’s really what these Coins represents. It’s about US Air Force Airmen… It’s about people & their airplanes/equipment that make the US Air Force what it is… THE BEST IN THE WORLD! WE VALUE YOU AS A CUSTOMER! We strive to deliver 5-star customer service, please contact me ASAP, if there are any problem so we can make things right…. THIS IS NOT A CHEAP CARNIVAL/MID-WAY. THIS IS THE “A GREAT DEAL”. REMEMBER YOU GET WHAT YOU PAY FOR! THIS IS THE REAL DEAL! This is an excellent gift for YOU or the love one on your list, to honor a special day or for any other gift giving occasion. This collector coin is the most desirable of all military coins & is considered the “crème de la crème” of service coins as born out by the exceptional detail and quality of embroidery and workmanship! The outstanding quality and detail in this coin will amaze you…. Coins are the perfect gifts for the special people in your life! A GREAT COIN FOR YOUR COLLECTION OR TO GO ALONG WITH MEMORIES OF TIME SPENT IN THE SERVICE! BEWARE OF COI N S THAT SELL FOR CHEAPER PRICES OR SECONDS THAT WILL FADE WHEN EXPO S ED TO SUNLIGHT! Land of the free… Because of the brave! We have staked the whole future of American civilization, not upon the power of government, far from it. Weve staked the future of all our political institutions upon our capacityto sustain ourselves according to the Ten Commandments of God. [1778 to the General Assembly of the State of Virginia] President James Madison made a major contribution to the ratification of the Constitution by writing, with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, the Federalist essays. In later years, he was referred to as the “Father of the Constitution, “. It is impossible to rightly govern the world without God and the Bible. Now, for the first time, you can enjoy that same quality merchandise, that we sell to our museum, wholesale & Navy unit accounts! Our specialty is authentic collector items supplied from the same patterns as the original units. GIVE US A CALL NOW AND LETS TALK ABOUT US MAKING YOUR CUSTOM PATCHES, PINS, HATS, & COINS FOR YOU OR YOUR UNIT OR REUNION! This coin is displayed proudly! Giving a coin, with a unit’s or individual’s insignia is a military tradition intended to readily identify past and present. This is an impact award for immediate excellence. It does not have to go through a bureaucracy. Giving it to others is a sign of mutual respect… And shows pride in the individual and the Unit! You’ll receive lots of compliments…. THIS IS A VERY HIGH QUALITY COLLECTOR COIN! This is the BEST COIN made period! Check out the complete tight pattern, detail trim, trend setting style of this COIN, unlike others for a cheaper price…. You get what you pay for! THIS COIN IS NEW AND IN MINT CONDITION. Great colors and design combine to make this COIN an instant classic. This is by far one of the best looking and exceptionally made coins out in the market and will make A GREAT GIFT THAT WILL LAST! This COIN IS A MUST FOR ANY SERIOUS COLLECTOR! This great COIN can be use d in a shadow box or display it as part of your military memorabilia collection. THIS COIN IS A GREAT SOURCE OF INDIVIDUAL AND UNIT PRIDE! If you do not see a COIN you want… We should be able to obtain one from one of our many sources. We have access to thousands of COINS or we can custom make a COIN… A COMMENT FROM ONE OF OUR GREAT CUSTOMERS! Rec’d the hat today… It’s the best. The bonus sticker was a real nice touch. I’ve learned my lesson and I’ll be back to shop with you again. I have left you positive feed back and would appreciate the same. Carl Nelson CPL – USMC 1983 – 1986 Weapons Co. 2/9 81’s Platoon. Our company provides both stock and custom Coins to Museums, Exchanges, Army/Navy stores, VFW posts, CAF Exchanges, Sea Cadet & Civil Air Patrol, Air Force, Navy, Air National Guard, Marine and Coast Guard Units world wide. REMEMBER: AMERICA IS NUMBER 1 THANKS TO GOD’S BLESSINGS! A FEW GREAT COMMENTS FROM A FEW OF THE FINEST! I thought that hat looked good on the web it is awesome, thanks man!!! You represent everything that is good about shopping with other veterans. Service was prompt the hat is excellent it arrived in perfect condition & the sticker & business card was a totally unexpected treat. I will be a multiple repeat customer & I will turn my buddies onto your e-bay store. I did my best there for you! Norm Copeland FTCS/SS USN RET. BE A FORCE MULTIPLIER! THE KENNEDY & REAGAN COLLEGE FUNDS THAN. Y & R E A G A N. IF YOU CANNOT FIND YOUR PIN OR PATCH… WE ALSO HAVE SPECIAL REUNION PRICING PACKAGE… BE SURE TO VISIT US AT AN AIRSHOW! A’Veteran’ — whether. Active duty, discharged, retired, or reserve — is someone who, at one. Point in his life, wrote a blank check made payable to’The United States. Of America,’ for an amount of’up to, and including his life. STOP BY & SEE US AT AN AIRSHOW!!!!!! We look forward to hearing from you TODAY! Please let me know if we can be of any other assistance. Thank you for your business, it is sincerely appreciated. We hope you will come back to see us again. Referrals are nice too….. The item “DESERT STORM VETERAN CHALLENGE COIN US MARINES NAVY ARMY AIR FORCE PIN UP GIFT” is in sale since Saturday, December 09, 2017. This item is in the category “Collectibles\Militaria\Desert Storm (1990-91)\Original Period Items”. The seller is “semperfimac.net” and is located in Lake Forest, California. This item can be shipped worldwide.